Luiz Irber > Talks > Petabase-Scale Search and Containment Analysis with Fractional Sketches

This is the text version of a talk I gave on 2022-08-30, at the JGI Annual User Meeting conference in Berkeley, CA - USA.

Petabase-Scale Search and Containment Analysis with Fractional Sketches

|

Hello! I'm Luiz Irber, and this is petabase-scale search and containment analysis with fractional sketches. I'm a computational biologist at 10x genomics, but today I'll be taking about the work I did for my PhD at the Lab for Data Intensive Biology at UC Davis, |

|

In collaboration with all these incredible people, including the FracMinHash parts with the Koslicki lab at Penn State, and the biogeography work with the Sumner lab at UC Davis. |

|

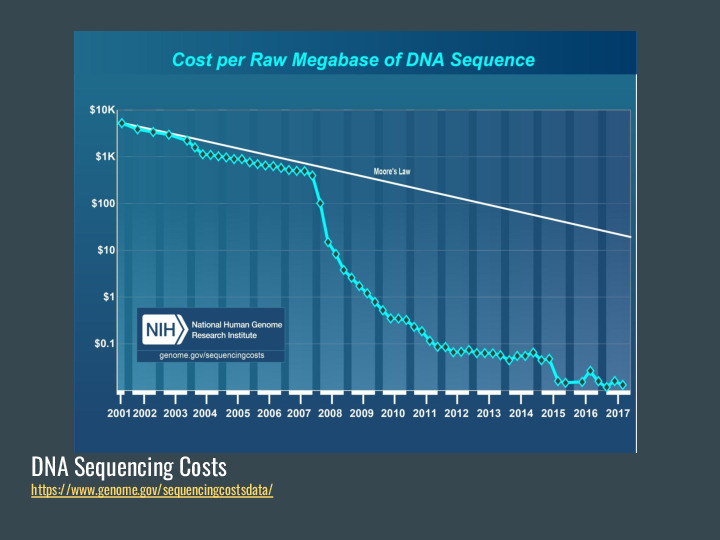

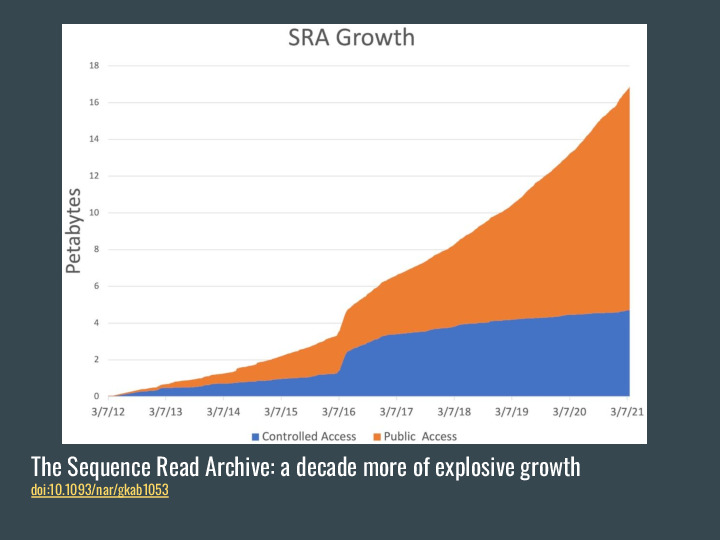

The motivation for this work is the flip side of this chart: as sequencing costs drop, we end up with a lot of data in public repositories. |

|

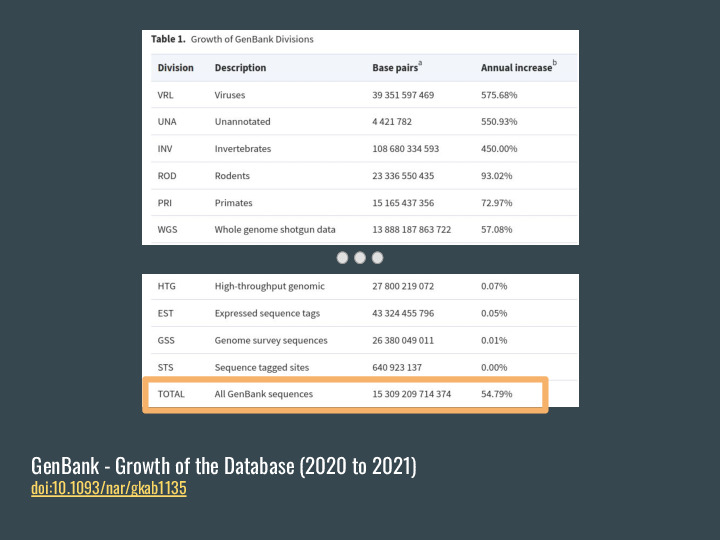

GenBank, for example, grew almost 55% between 2020 and 2021, to 15 TBp, and |

|

the SRA was approaching 18 PB of data last year. |

|

And so, how do we deal with the data deluge? In this talk I'll present lightweight approaches for data analysis, focusing on sketching and streaming methods, The general workflow is narrowing the amount of data to be analyzed to a smaller subset that is useful for deeper exploration, because not many people have 25PB available to store all this data. To do that we might need to rephrase research questions a bit, so let's go through one example. |

|

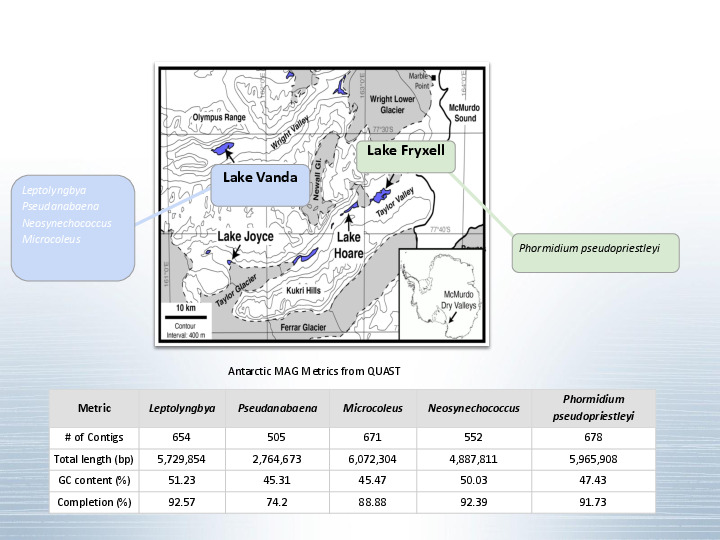

Let's say you sample a remote environment like Lake Vanda in Antarctica. |

|

Jessica and the Dawn lab analyzed and extracted 5 new metagenome-assembled genomes, each one ~5 MBp long. But... There aren't other assembled genomes for these specific cyanobacteria to compare against. At the same time, there is a lot of public metagenomic data in the SRA, around 700 thousand datasets totaling almost a petabyte of data. What if we took these MAGs, and checked if we can find very similar organisms in all this data? |

|

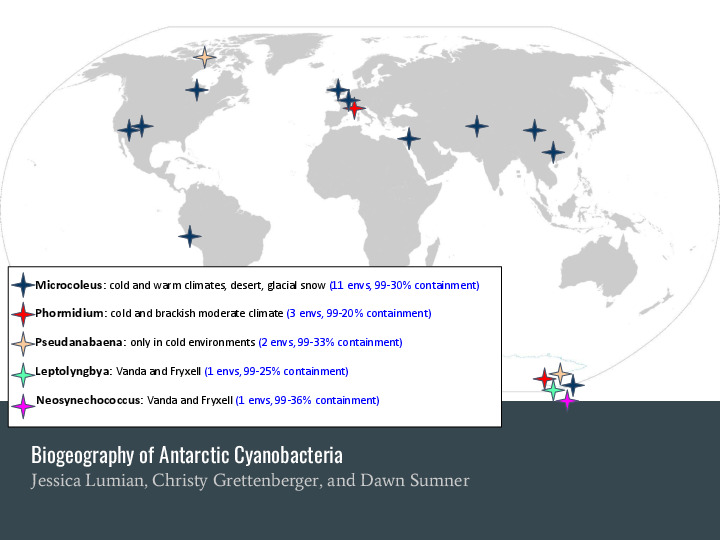

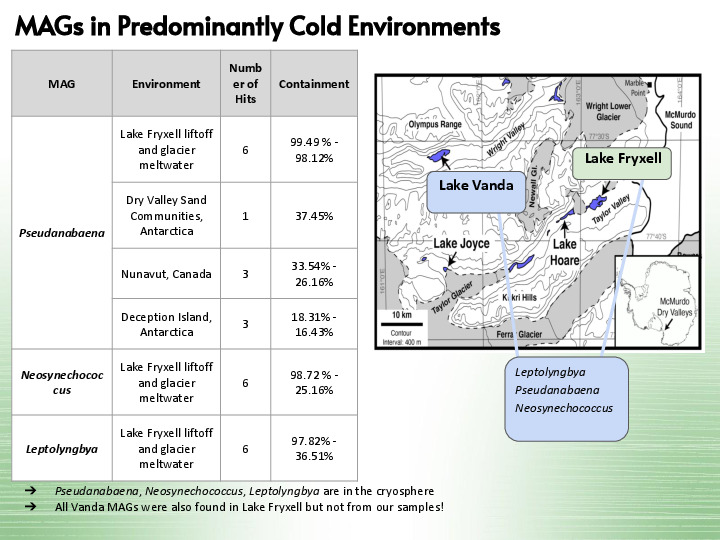

That's what Jessica found: there are similar organisms spread through many environments! These two bottom ones, for example, |

|

Are from the same environment, but from a different study, so more data to refine the MAGs. The first one is also present in an arctic environment, so all three MAGs are in predominantly cold environments. |

|

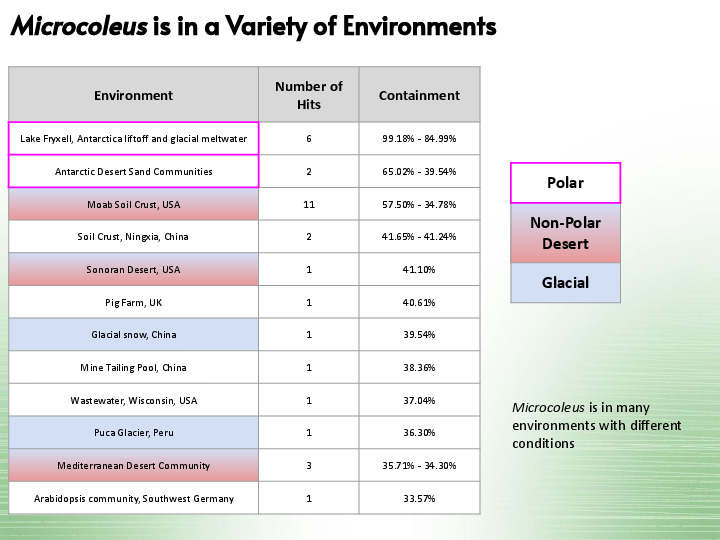

Our next MAG is in a variety of environments, from glacial snow to deserts. |

|

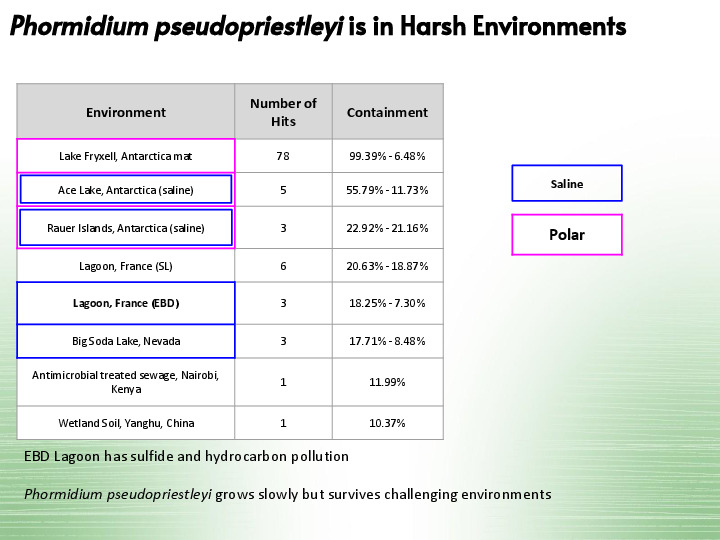

And our last one is present in harsh environments, including a lagoon in France that has sulfide and hydrocarbon pollution. |

|

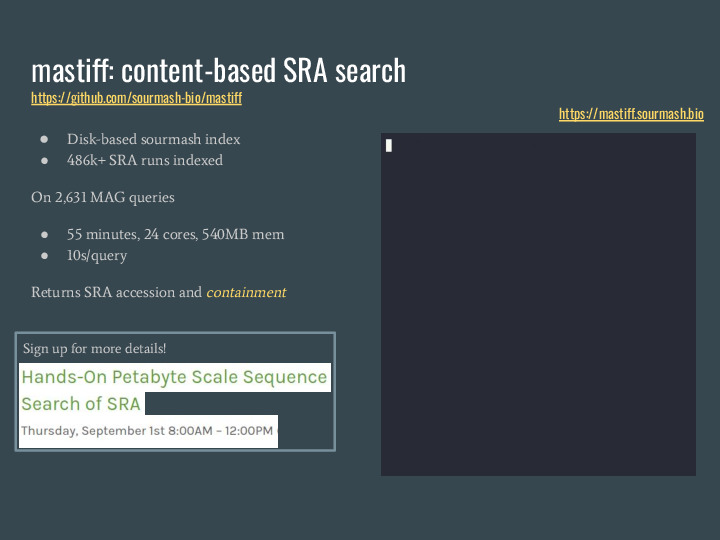

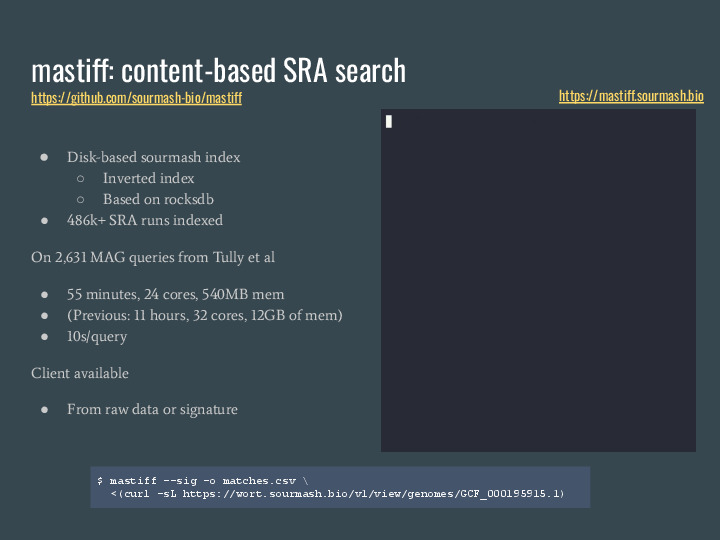

Jessica used a method developed in the DIB Lab called On the right you can see an example running a query for a MAG in real time, taking about 4s. I also ran it over 26 hundred MAGs and it took 55 minutes using 24 cores and 540 MB of memory, which is abot 10s per query. This tool returns an SRA accession and the containment of the query in the accession, and we will be using it on the workshop on Thu (sorry, you can't sign up anymore!) |

|

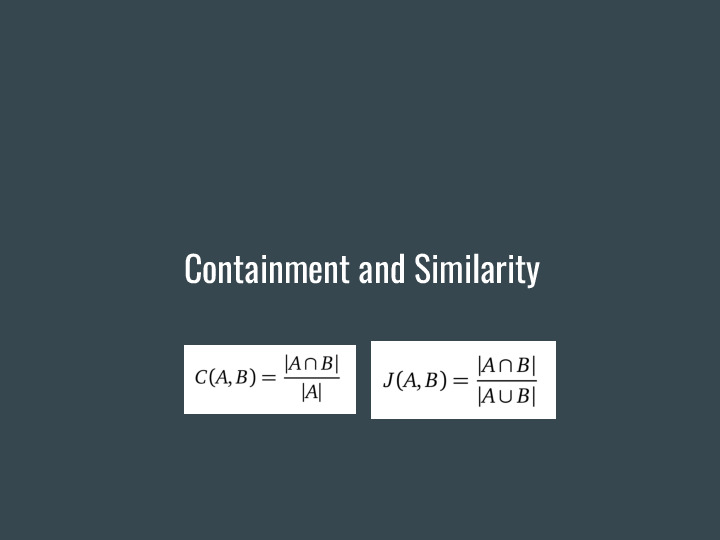

Let's dig a bit deeper into what containment is, and how it enables these searches. Containment is related to another metric called Jaccard similarity, |

|

Which measures how similar two items are to each other. Using sets, it is a ratio of the intersection of the items over the union. This works very well when items are about the same size. |

|

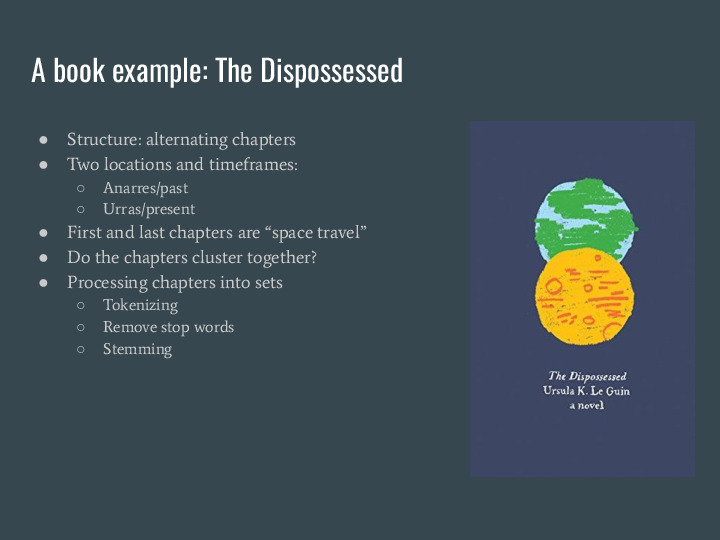

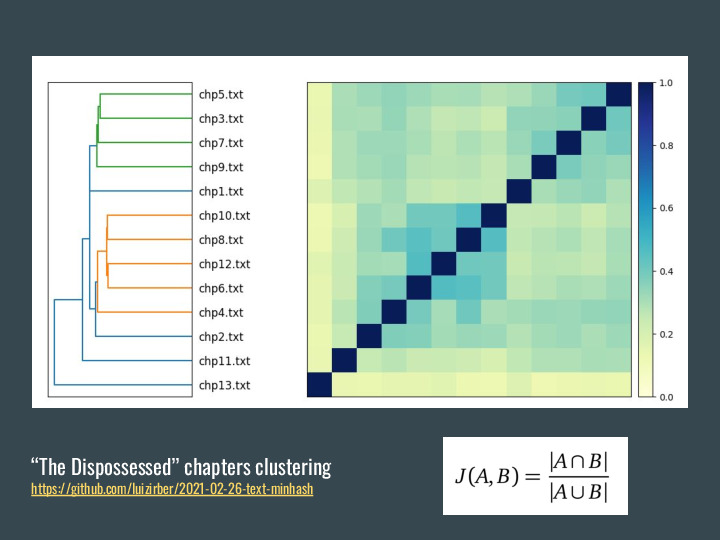

Using a book example: The Dispossessed is a novel by Ursula K Le Guin, and is structured in chapters of similar lengths. They alternate between two planets and timeframes, with the first and last being space travel chapters. And so I wanted to know: do the chapters cluster together? The first thing to do is processing the chapters into sets. For that we tokenize the text (split into words), remove stop words (like "the") and can also do stemming to have the root of the words. |

|

Once we do that, we can apply similarity and they do seem to cluster, with odd and even chapters in different groups. |

|

Containment, on the other hand, is a better measure to answer how much of one item is present in another. Again using sets, it is a ratio of the intersection of the items over the size of one of them. This gives us different results, unless both items have the same size. |

|

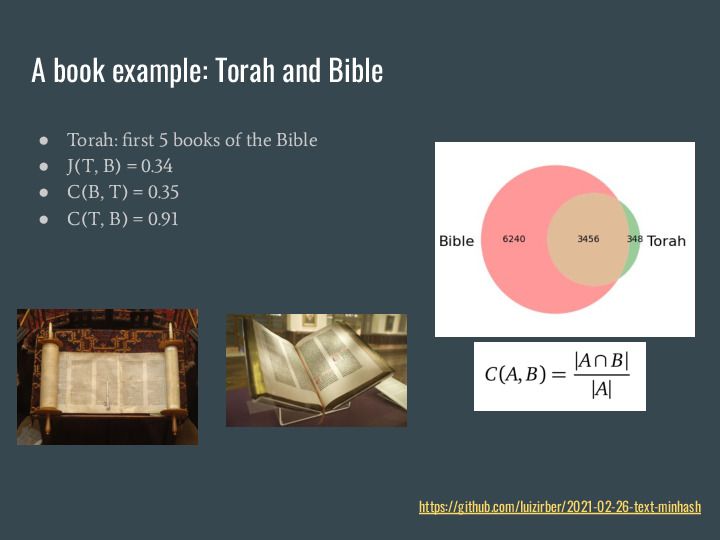

Again for a book example, we can use the Torah and the Bible. The Torah is the first 5 books in the Bible, so if we use the same process for transforming into sets and calculate the similarity we see it is about 34% similar. If we calculate the containment of the Bible in the Torah is it about the same, 35%. But the containment of the Torah in the Bible goes to 91%. |

|

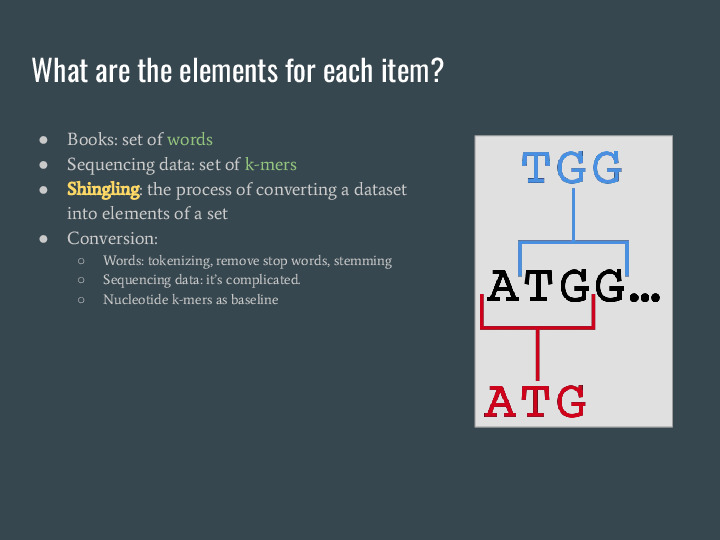

For these examples I'm using books, but we can do the same with sequencing data. While we don't have a clear equivalent to what we did with words, we can use nucleotide k-mers for this shingling process, a fancy name for the conversion of a dataset into elements of a set. |

|

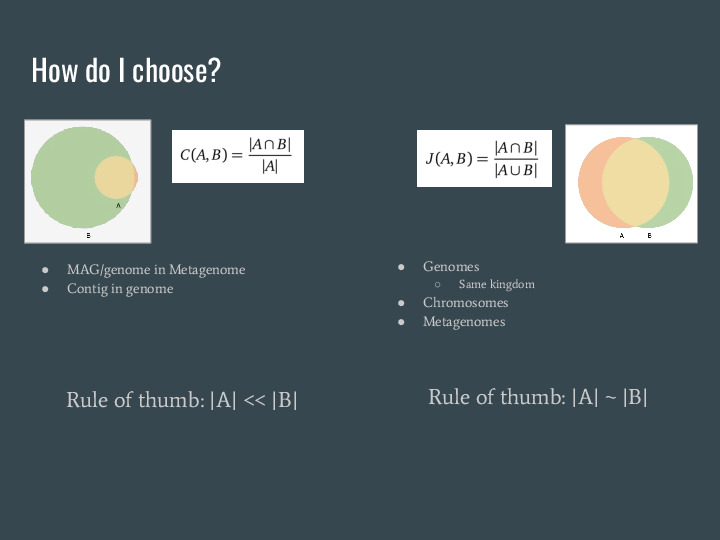

So, when to use each one? Containment is better when one thing is much larger than the other. So it works better when you try to measure how much of a MAG or genome is in a metagenome, or a contig in a genome. Similarity is better when things have the same size. This can be genomes (in the same kingdom), or chromosomes in a genome, or different metagenomes. |

|

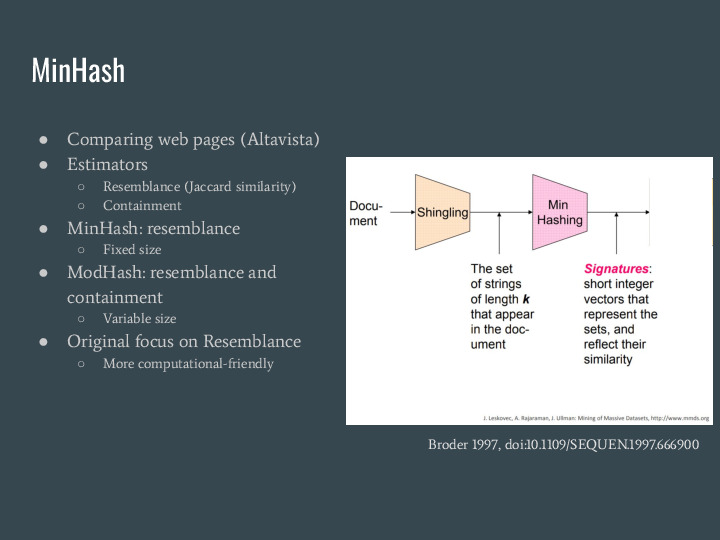

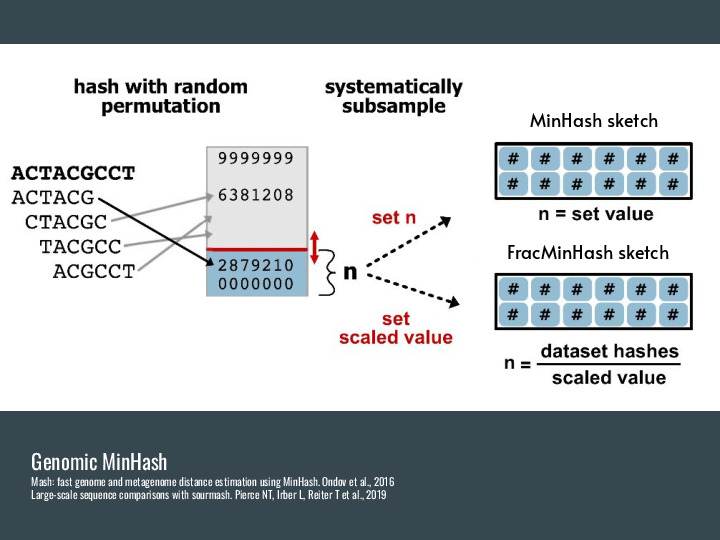

Building sets for all the k-mers is expensive. But there is a technique from 1997 originally developed for comparing web pages called MinHash that provides estimators for similarity and containment using much less space. |

|

This was applied in genomic contexts by Mash in 2016, and the basic idea is to use a hash function to convert k-mers into a hash (an integer), and then pick a fixed number of these hashes as a representation of the original data. FracMinHash is an alternative developed in the lab that picks every hash below a threshold, and so isn't fixed-sized anymore. But it is still a fraction of the original data, and you can use this scaled parameter to increase precision (at the cost of memory/space usage). Turns out you can use this subset to estimate similarity and containment pretty well, and it is much smaller than the original data. |

|

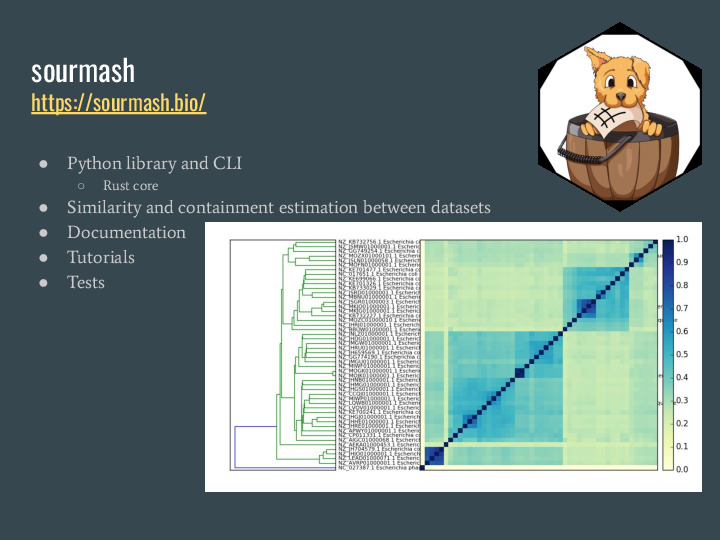

sourmash is a software package implementing FracMinHash and associated methods as a Python command-line interface and library (with a Rust core) that allows similarity and containment estimation between datasets. We have documentation, tutorials and a development process including tests, continuous integration and frequent releases. |

|

We have over 37 code contributors, and many more users that help guide where we go with it. |

|

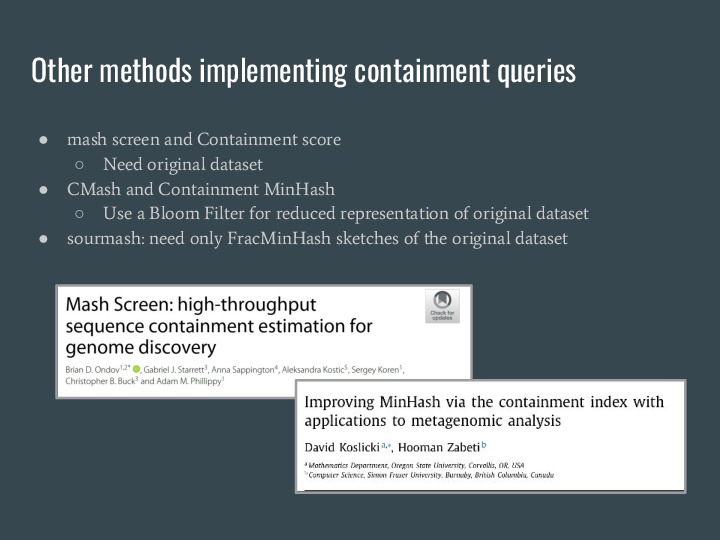

There are other methods that also allow estimating the contaiment, but they either need the original data for the query or other sorts of reduced representation like Bloom Filters. |

|

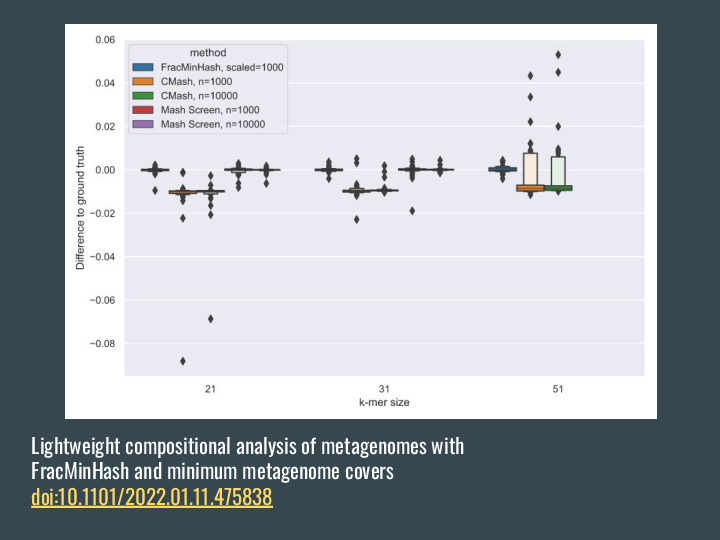

They all work great! If you compare the containment estimation with the ground truth using all the k-mers, they are all very close. |

|

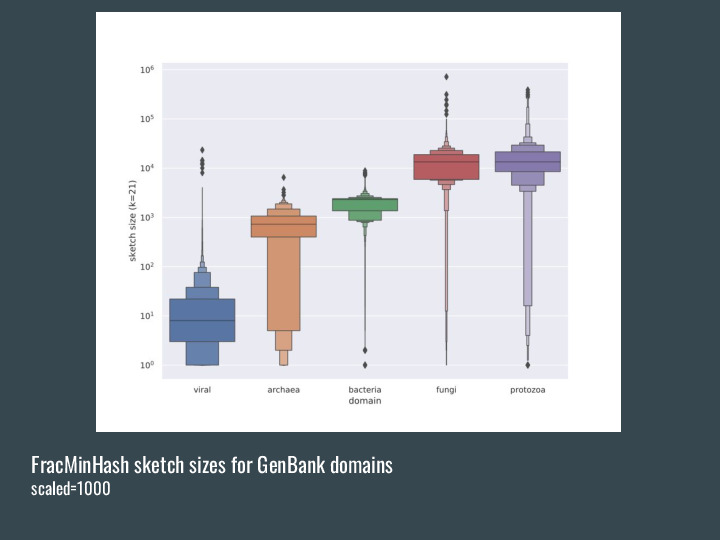

But while the other MinHash-based methods have fixed size for the sketches, FracMinHash grows larger with the complexity of the original dataset. So a metagenome will be much larger than a bacterial genome. |

|

And allow other operations like subtraction and abundance filtering. This scaled parameter also allows trade-offs between precision and resource consumption, with lower scaled values giving more precision for smaller queries (like viruses) and larger scaled values allowing faster processing and less memory (good for metagenomes). |

|

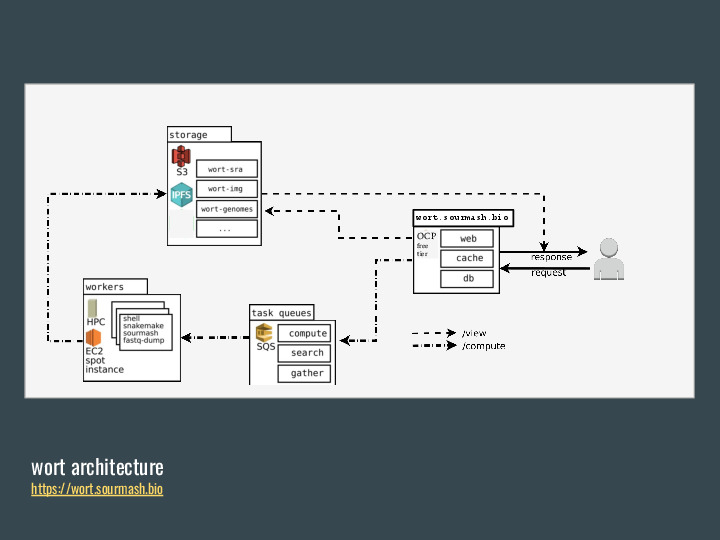

OK, so FracMinHash is nice. Wouldn't it be great if we didn't have to download the full datasets and calculate it ourselves? And so wort was born, as a system for calculating FracMinHash sketches from public genomic databases. |

|

The idea is to submit requests to build signatures for public datasets, which go into queue. Distributed workers pick jobs, download the sequencing data, and calculate a signature. Then they send the signature to an S3 bucket, which is also mirrored on IPFS, and made available for download. The workers currently run in a mixture of HPCs, local workstations and cloud instances. |

|

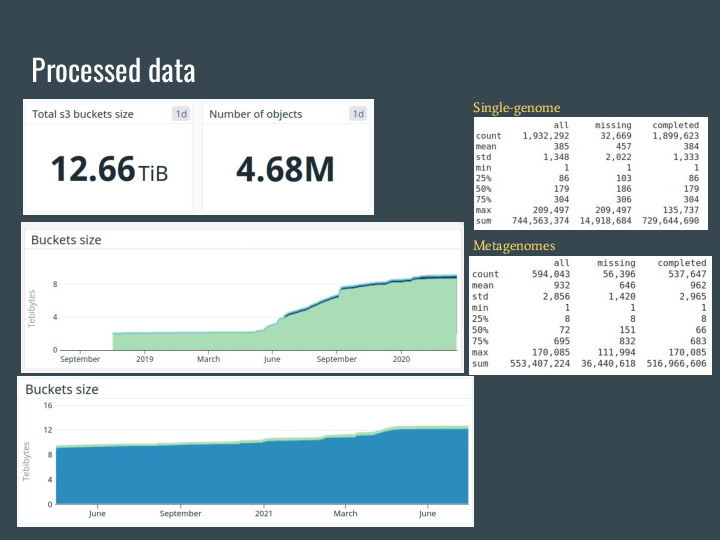

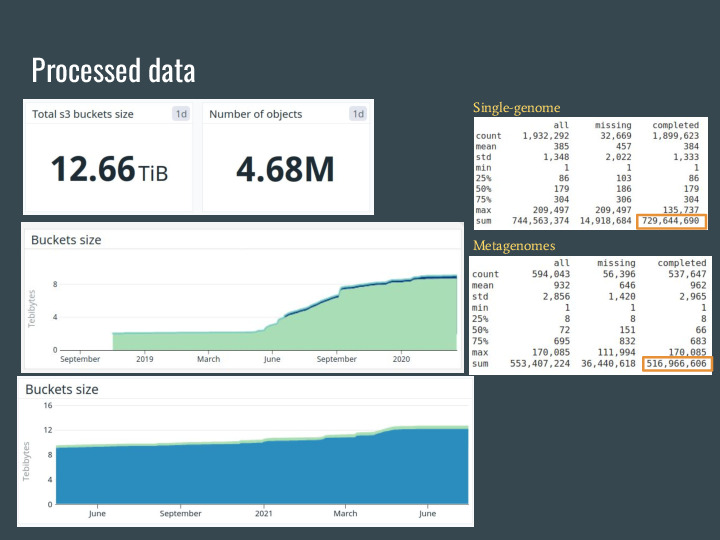

These slides are from two weeks ago, and now wort is over 13TB of signatures from over 4.7 million datasets from the SRA, GenBank, RefSeq and IMG. |

|

The original data is over 1.3PB, so the petabyte-scale from the talk title is accurate =] |

|

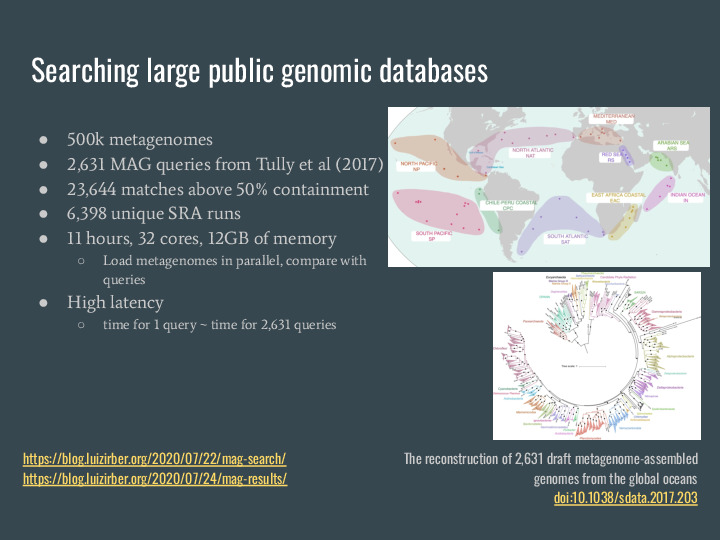

Two years ago, while I was writing my dissertation, I wanted a use case for this pile of data, and so I came up with this MAG search idea. Turns out that building a sourmash index was prohibitive (it's over 700GB of signatures), so I ended up doing a massively parallel search over the 500 thousand metagenomes. It took a week to implement and get results back. As a query I used the 26 hundred MAGs from Tully 2017, and got back 23 thousand matches over 50% containment, from 63 hundred thousand SRA runs (excluding TARA and other runs used for building the MAGs). It took 11 hours on 32 cores, using 12GB of memory. The largest drawback, other than the runtime, was the high latency: the time for 1 query is about the same for 26 hundred queries. |

|

Two months ago I tried out an idea that was in the back of my mind for a long time: what if I use rocksdb, an embedded disk-based key-value store, to build an index? And so mastiff was born. It is a large index (over 600GB), but since it is on disk it can be loaded on demand. Now it takes 10s/query (against 2 minutes from the previous approach), with very low latency. There is a command line client available that will calculate a signature for your data if you don't have one. And combined with wort you can do one liner like this one, which downloads a RefSeq signature from wort and search for matches using mastiff. |

|

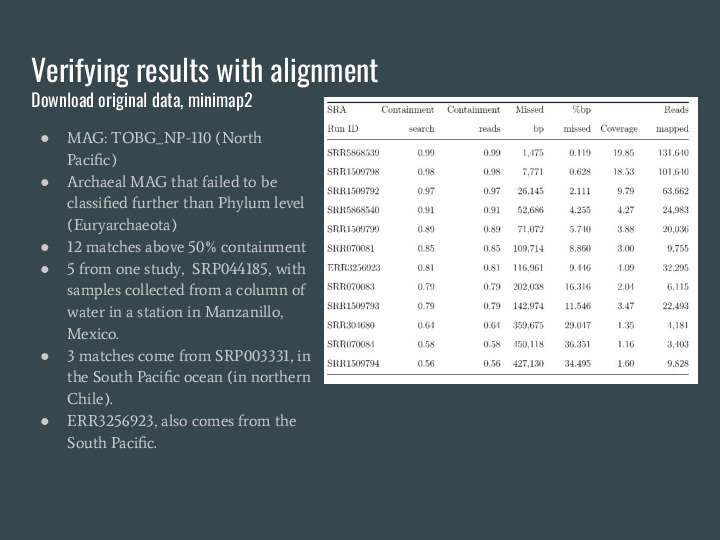

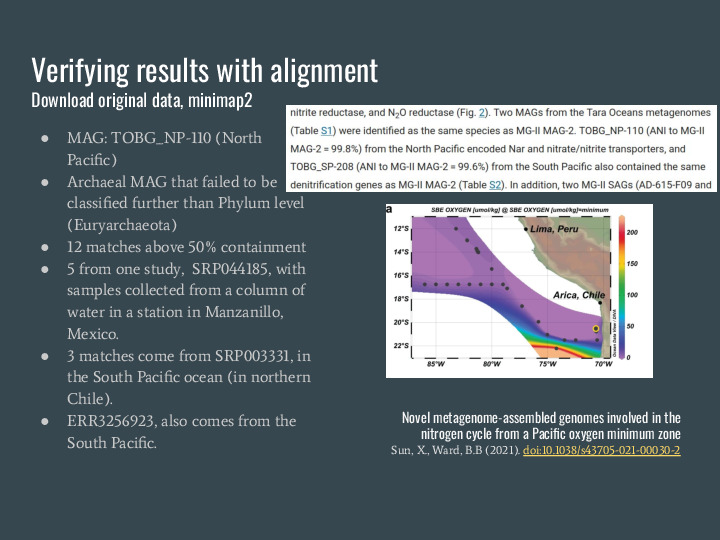

To verify the results from this MAG search I picked one of the MAGs, TOBG_NP-110, an archeal MAG that failed to be classified further than the Phylum level on the original analysis The NP stands for North Pacific. I downloaded the metagenomes and used minimap2 to verify containment, and they match, which is a great validation of the estimator because you can see it matches exactly. |

|

But even cooler is that I was preparing this presentation and a couple of matches in the South Pacific are very close to this other article published last year, which did new sequencing and found the same species in the same spot! |

|

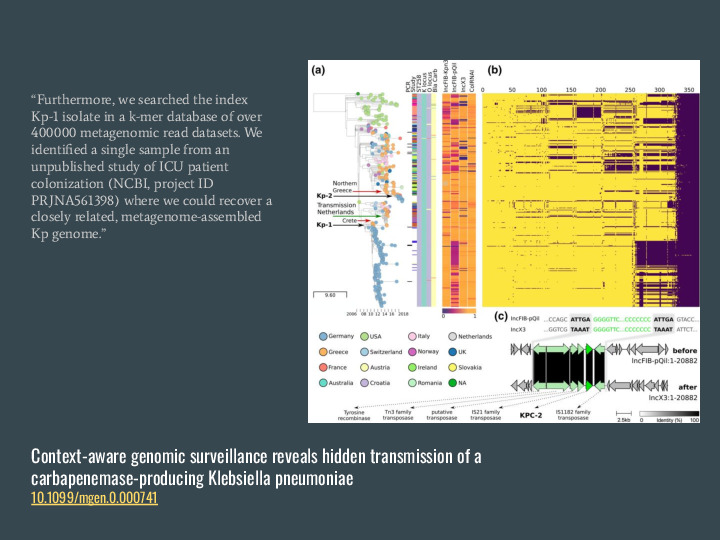

Another cool result is from this collaboration that investigated a Kp outbreak in Europe and found a closely related genome match in the US, which was totally unexpected. |

|

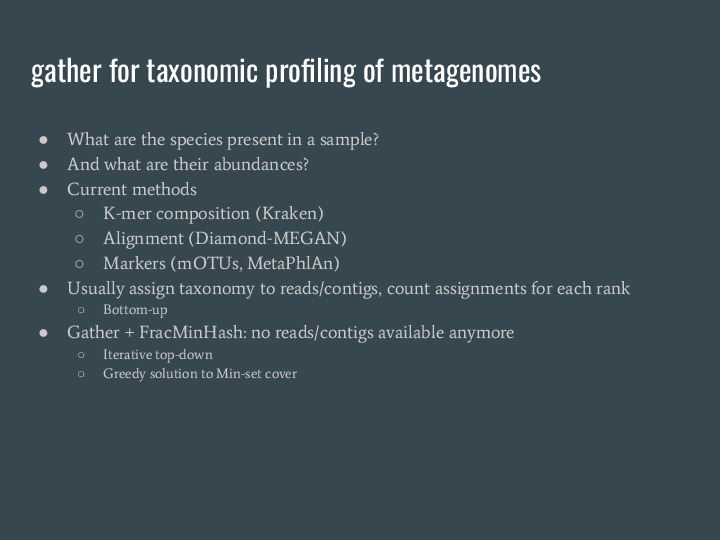

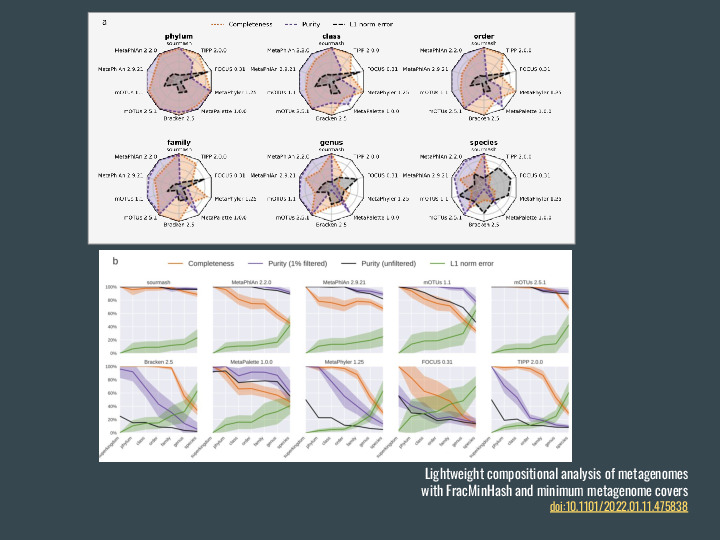

Deviating a bit from large scale search, I would like to mention a couple of other analyses that can be done with FracMinHash, starting with taxonomic profiling of metagenomes. Gather is a method for finding min-set covers for a dataset. Using a metagenomes as query and coupling with a reference database for genomes it can identify which genomes are present in the metagenomes, and what is their abundance. |

|

We compared it to other taxonomic profilers and it performed pretty well, using reference databases containing many more genomes than other tools. |

|

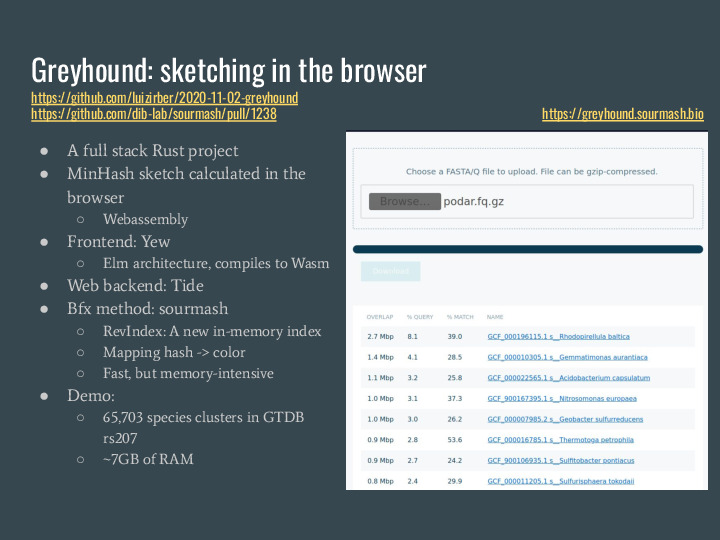

A puppy-sibling of mastiff is greyhound, which is in-memory only but very fast. I prepared a demo using the 65k species clusters from GTDB rs207 and provided a web interface for building sourmash signatures for your data locally in the browser, and sending the signature to a server for running gather. This server uses about 7 GB of RAM for the index. (And mastiff will get a web frontend too, I just ran out of time to build it for this presentation) |

|

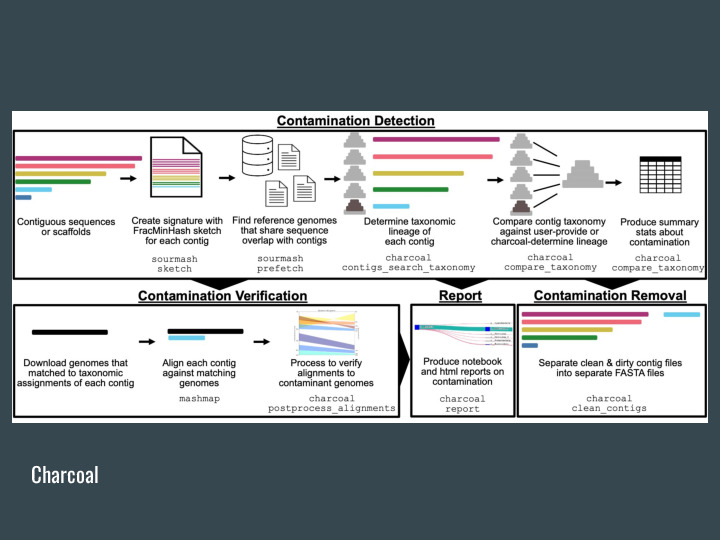

The gather algorithm can also be used for detecting contamination in genomes, charcoal is the project doing this in the lab. |

|

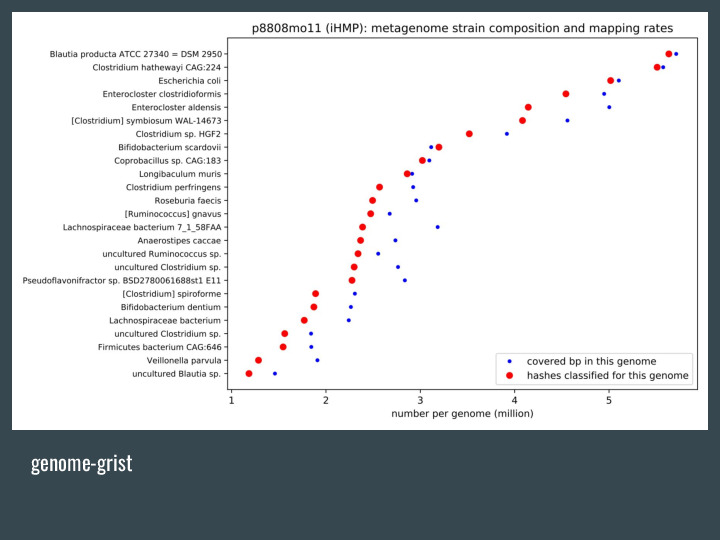

Genome-grist is a pipeline that automates a lot of these metagenome-related queries, like downloading the data from the SRA, and generate some plots and summary info. |

|

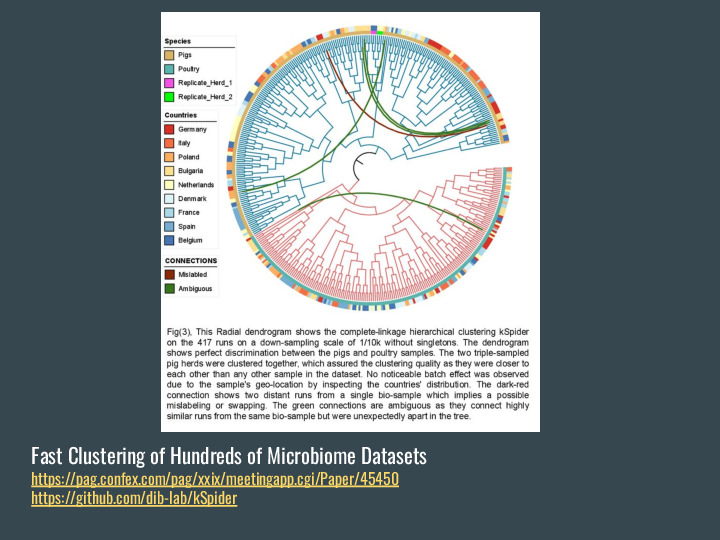

There are also projects in the DIB Lab using FracMinHash sketches, like the new version of this fast clustering of hundreds of microbiome datasets. |

|

And that was a whirlwind of information, so thanks for sticking around, and feel free to contact me or any of the other sourmash developers for more information! |